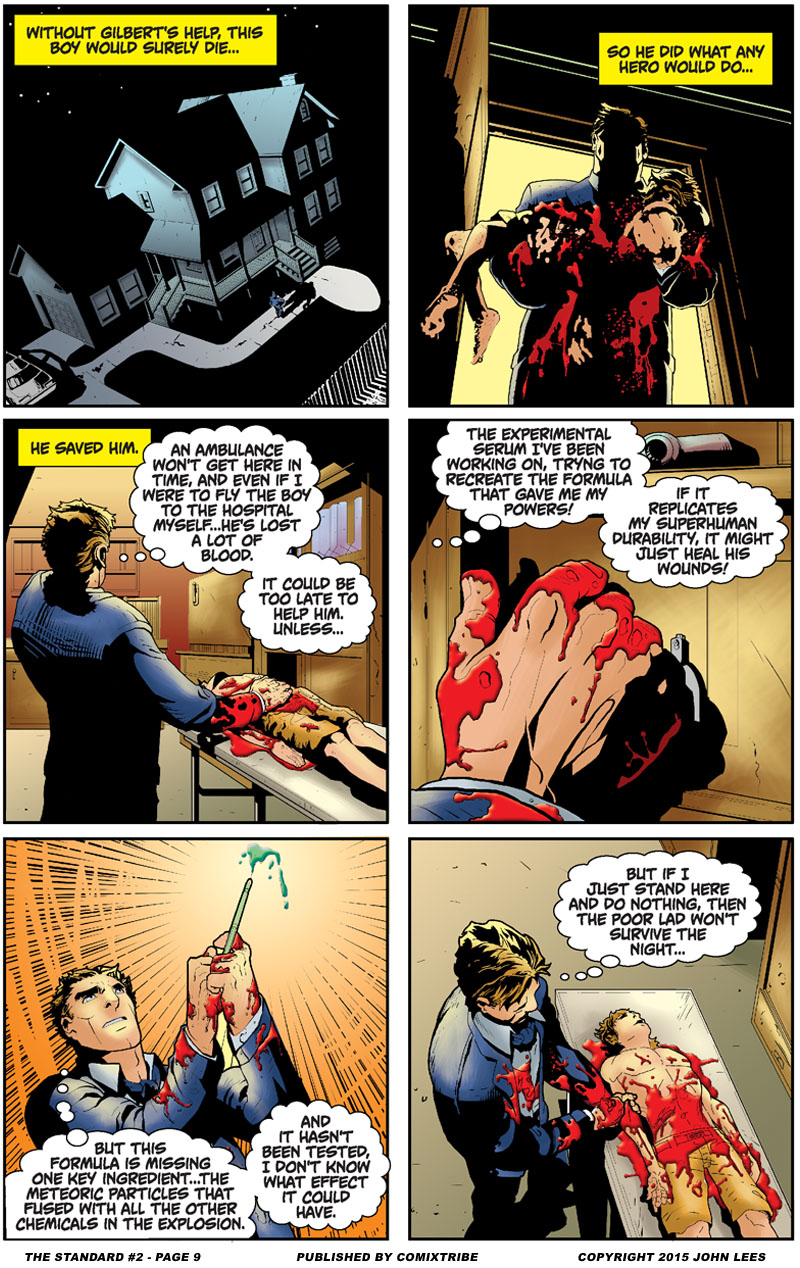

The Standard #2 – Page 9

Here, one page after we saw Gilbert in the present learn of Alex’s death, we see a younger Gilbert save Alex’s life. From this moment, Gilbert would feel responsible for Alex’s life… right until the end of it.

There’s relatively little direct commentary I can think to add to this page – save for noting how much fun it is using thought bubbles! – so i thought I’d dredge something up from the archives and share some content I’d originally posted on the official blog of THE STANDARD when filling in the in-universe history of our hero. Here is some historical commentary on Gilbert Graham’s tenure as The Standard, and the role he played in the Vietnam War:

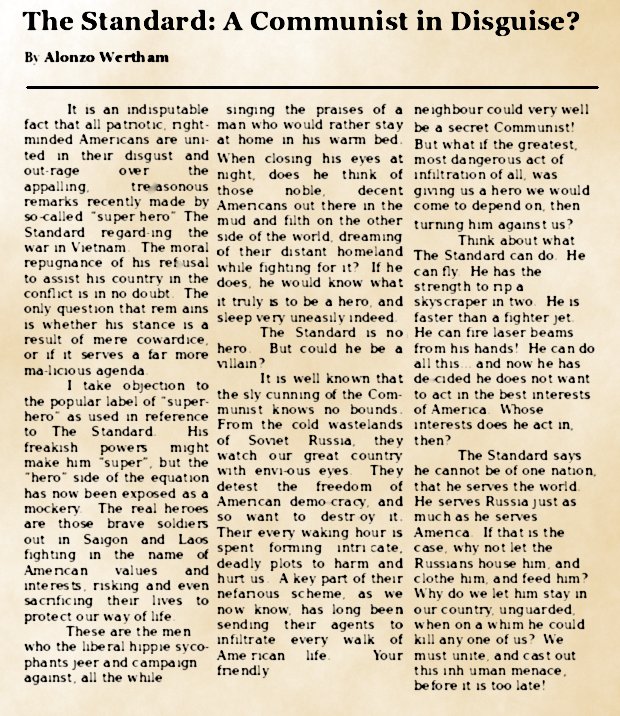

As mentioned earlier in this blog, the superheroes of the comic books had originally been an invaluable propaganda tool during World War II. They encouraged readers to buy war bonds, or even to take a go at punching Hitler on the jaw themselves. So inevitably, when America found itself with a real-life superhero, one of the first questions on many people’s lips was what role this masked defender of the people would play in the war in Vietnam the country was currently embroiled in.

It was a question that went unanswered, for a time. The Standard stuck to fighting crime in Sky City and elsewhere in the United States, and made no mention of the conflict in Vietnam. And that was fine at first. The question of how a being of The Standard’s power and invulnerability could affect the outcome of the war was more a topic of curiosity than anything else, though his image was quickly incorporated into propaganda of the time, as can be seen by this unfortunate recruitment poster:

But that changed with the Tet Offensive in 1968, with US involvement reaching fever pitch and all available resources being called upon to support America’s cause. It was at this point that The Standard was officially called to fight for his country. And when put on the spot… The Standard refused.

It sent shockwaves through the nation, and brought with it a wave of controversy. In a brief public statement, The Standard had this to say:

I took this mantle to inspire the world, and in that way, yes, to bring change. But to enter the global stage, affect the outcome of wars… that is not the change I seek. To operate on such a scale would be to potentially interfere with the course of history. Furthermore, it involves making me an agent of political agendas and national interests, which defeats the very purpose of what I seek to be. I am a proud American, but The Standard cannot be of one nation. Sky City may be my home, but I serve the world.

Backlash against The Standard was harsh. Many critics called him unpatriotic, a draft dodger, a coward, even a communist. In many circles, his popularity plummeted to an all-time low. There were times when he would show up to rescue people from a fire or stop a bank robbery, and the onlookers would boo and jeer him, even throw things at him. In one infamous public altercation, police officer Donald Humphries tried to arrest him for treason. When handing over some crooks to the authorities, Humphries placed handcuffs on him and called him a worse kind of criminal than those he was chasing. The Standard simply broke the handcuffs and flew off. There weren’t really any grounds to arrest him: his identity was unknown at the time, so he couldn’t officially be drafted.

It must have been hard to stick to his principles against such anger. But he did. And he wasn’t without support. Certain circles commended him for his diplomacy, and foresight in recognising the implications of someone like him getting involved in conflicts such as these. Interestingly, however, when certain student groups requested The Standard’s presence in anti-war protests, he politely turned them down, saying that he had nothing but admiration for the soldiers brave enough to risk their lives for their country, and he would not be part of anything that disrespected them.

With the disaster that the Vietnam War turned out to be, The Standard was ultimately vindicated in his decision to steer clear of it. Other superheroes who did get involved in the war – mainly patriotic-themed heroes such as Colonel Yankee or the flag-waving trio Red, White and Blue – found their credibility permanently tarnished upon their return. The Standard, meanwhile, weathered the initial storm of divided public opinion, and emerged on the other side as beloved as ever, his legacy intact.

Much has been said over the decades about The Standard’s stance of non-intervention in The Vietnam War. But there is a second side to this story, one that has received less coverage, but is just as – if not more – significant in grasping an understanding of The Standard’s motivations. We discussed earlier what The Standard’s response to Vietnam was, but what about Gilbert Graham?

At the time he first became The Standard, Gilbert Graham had been working as a scientist, doing advanced chemical research. As The Vietnam War wore on and the Tet Offensive got underway, at the same time as The Standard was facing public pressure to fight for his country, Gilbert Graham was commissioned by the Government to develop chemical weapons for the US Army to disperse in Vietnam. Dr. Graham refused, fearing the terrible, long-ranging consequences such attacks could have on the people of Vietnam for generations to come: in this regard too, history would eventually prove him right. But his refusal to cooperate cost Gilbert his job, and for a time, some degree of public disgrace. With the shaming he got in the press as a traitor and possible Communist sympathiser who callously refused to help the US Army, he could not find work anywhere in the field again. It reached a point where he was even mentioned by acting Senator at the time, George McColl:

It shows a distinctly shameful breed of cowardice to have within your means the ability to aid your fellow countrymen, and instead do nothing. Gilbert Graham sits safely at home while young Americans die on the other side of the world, and he spares not a thought for them.

Gilbert was reportedly very shaken by this condemnation, yet for some time never spoke out in detail about why he was supposedly abandoning his countrymen to die unaided. And so the Senator’s jibes were, for most people, the last word on Gilbert Graham and his involvement in Vietnam.

But that is not the whole story. For many months later, when any notoriety he may have gained had died down, Gilbert Graham quietly enlisted, and was dispatched to Vietnam, serving for three tours of duty. Gilbert has never spoken of his time in Vietnam, so his motives can only be speculated on. But if this historian were to speculate, he would suggest that perhaps though he could not abuse his status as The Standard or his skills as a scientist in affecting the outcome of the conflict, and despite any objections he may have had to the validity of America’s involvement in the war, Gilbert Graham could not allow people to die while he did nothing. It is in his nature to help people, to make a difference and do good wherever he can. It’s what made him become The Standard in the first place. With the moral quandary he was in, the most he could do was simply be there with the young men fighting for their country: no chemical weapons, no superpowers, just him.

Here is one final footnote to this story, perhaps the most astonishing detail of all. All through this time while Gilbert Graham was serving in Vietnam, the activity of The Standard back in Sky City, USA went on undiminished. He could not abandon his countrymen like Senator McColl had once accused him of doing, but neither could he abandon his city, and the icon of hope and compassion he had created in The Standard. The whole world thought that The Standard had made a choice between fighting for his country and being a hero that stood above war and politics. But in truth, he managed to do both.

Discussion ¬